Writings and Articles

Do you know what the symptoms of trauma actually look like?

by Carmen Littlejohn

Being a psychotherapist that specializes in trauma, I have a unique opportunity to study the effects of trauma on the brain, on the body, and on the client’s subjective experience of the world. I think it is very important for the world of medicine and psychology to understand trauma in a deeper way, so that we can properly diagnose it and help our clients heal faster.

We tend to think of trauma as a war, car accident, or sexual abuse. This isn’t entirely true. Trauma is not the actual event that happens to the person. Trauma is the reaction of the brain being overwhelmed by the event. When fear or negative emotions overwhelm the brain, it needs to find a way to protect itself. This is the experience of trauma. The protection of the brain is automatic, not a conscious decision. To handle the experience, the brain will often split the experience up into many different parts and store them in the brain separately. “The traumatizing event results in memories that are stored in a dysfunctional way, that is, stored in isolation, unassimilated into the memory networks of the individual. The lack of adequate assimilation means that the client is still reacting emotionally and behaviorally in ways consistent with the moment of trauma” (Shapiro, 2001, p17).

Trauma, therefore, is a subjective experience. What overwhelms one person’s brain may not overwhelm another person’s brain. Also, what overwhelms a child will, very likely, not overwhelm an adult. A child is more susceptible to trauma because the child is not born with natural defenses to protect itself. As we get older and become adults, we become much more skilled in protecting ourselves, managing emotions, and setting boundaries. We are not as vulnerable to trauma. That is not to say that adults don’t experience trauma, just that adults are not as susceptible to trauma.

In the psychology world we have been talking about “big T” trauma and “little t” trauma for years. We know that having a “big T” trauma like war, car accident, or sexual abuse can create trauma in the brain. However, neuroscientific research has now shown that the “little t” traumas of childhood, often called attachment trauma, are just as harmful to the brain. For example, a child that constantly feels physically threatened, a child that finds themselves alone too much, or feeling like they don’t measure up in their parents eyes, we call this attachment trauma, as it relates to the attachment relationship of the primary caregivers and the feeling of safety and security of the child. The amazing thing about trauma is that the threat doesn’t have to be real to cause harm, just the perception of threat is enough to cause an overwhelming fear reaction in the brain.

Surprisingly in clinical work, “little t” or attachment trauma can be harder to resolve than “Big T” trauma; mostly because of the consistent nature of it. Research shows that this consistent type of trauma affects the brain even more because it is forming the child’s experience of life, safety and love. Some of the symptoms I often see in these patient’s lives are mental, physical, and relational.

Mentally, I see that the client may have abnormal amount of fears and phobias, chronic patterns of anxiety and hyper-vigilance, addiction issues, and a higher dependency on drugs. They suffer more from depression, personality disorders, and thoughts of suicide. Their symptoms may be misdiagnosed as ADD. Physically, I see all kinds of somatic symptoms: stomach issues, auto-immune diseases, poor posture, and chronic pain responses. Relationally, they are often in relationship dynamics that are unhealthy in some way. They may identify as a savior type or needing a savior to rescue them and keep them safe. They may have people-pleasing tendencies or rebel at authority. They may often feel overly helpless, get easily overwhelmed, feel like a victim, or always need to be in control.

We don’t tend to think of these symptoms as symptoms of trauma, but they are. Because trauma doesn’t reside in the thinking part of the brain, we can’t treat trauma by talking about it or taking medication to stop the symptoms. The trauma lives in the middle and lower centers of the brain, where the survival and reactionary parts of the brain are. When these parts of the brain get triggered our emotions get triggered and then our thoughts get triggered. To resolve this dilemma, we need to work from the lower brain up to the higher brain. This means getting to the unconscious and automatic responses that are outside of the individual’s cognitive awareness and working up towards their thoughts and cognitive schemas.

PTSD:

Under-diagnosed, under-treated, under-estimated

by Carmen Littlejohn

What is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder?

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can develop after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, or learning that a traumatic event has happened to a loved one. DSM5 defines a traumatic event as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

Following the event, people with PTSD report intrusive symptoms such as repetitive and upsetting memories that can present verbally, “I can’t stop hearing that crunch noise when the car hit the tree,” or acted out in play such as a child repeatedly hitting a toy car against the wall. Other intrusive symptoms include distressing and vivid night and day dreams or flashbacks, and becoming highly distressed when exposed to reminders of the event. They can also avoid or try to stay away from any reminders of the event, report inability to recall significant details of the event, experience a range of negative emotions such as sadness, guilt, shame, and confusion, and lack interest or desire to participate in important activities. They may also experience irritability, being jumpy or on edge, trouble concentrating, and sleep difficulties. Some people may experience a delayed reaction to the trauma so that clear signs are not noticeable until months or even years after the event.

1. Recurring thoughts, ‘flashbacks’ or nightmares about the event (Each person’s experience with flashbacks is unique. Some people have “complete” flashbacks, while others may re-experience a feeling, smell, sight or sound from the event without losing touch with the present. You may not even know you’re having a flashback.)

2. Changes in sleep patterns or appetite

3. Anxiety and fear, especially when confronted with events or situations that remind you of the trauma

4. Feeling “on edge,” being easily startled or becoming overly alert

5. Crying for no reason, feeling despair and hopelessness or other symptoms of depression

6. Memory problems including finding it difficult to remember parts of the trauma

7. Feeling scattered and unable to focus on work or daily activities

8. Difficulty making decisions

9. Irritability or agitation

10. Anger or resentment

11. Guilt

12. Emotional numbness or withdrawal

13. Sudden over-protectiveness and fear for the safety of loved ones

14. Avoidance of activities, places or even people that remind you of the event

15. Physical health problems like dizziness, stomach upset or decreased immune system

Thoughts (Note young children they may be unable to identify specific fear thoughts):

It’s my fault it happened

All men are dangerous

I need to stay alert at all times to protect myself

I deserved it, I’m a bad kid

Physical sensations:

Stomachache, headache, muscle tension, irritability, feeling amped up, feeling detached from one’s body

Emotions:

Sadness, anger, shame, guilt, anxiety, fear, panic, confusion

Behaviors:

- Avoiding participating in new activities or going places

- Refusal to sleep alone or trouble falling/staying asleep

- Asking a parent to be present or available

- Recreating the traumatic event through play

- Crying or tantrumming

- Restricted play

- Trouble concentrating

- Aggression and hostility

Common Situations or Affected Areas

- Avoiding contact with, or reminders of, the traumatic event

- Declining grades or academic failure

- Engaging in high risk or dangerous behaviours

- Trouble making friends, dating, and development of meaningful relationships

- Restricting life plans or reduced ambition

- Social withdrawal

How PTSD impacts the child at different ages

Children may show their symptoms of PTSD in different ways:

1. Fear of strangers.

2. Fear of family members.

3. General avoidance of situations that are not related to the trauma (for example, avoiding going to school, going out in public).

4. Traumatic play; re-enacting parts of the trauma in their play (drawings, acting out).

5. Regressive behavior (thumb sucking, bed-wetting).

6. Omen formation: This is the belief that there were "warning signs" before the trauma occurred. Children with this belief are always on the alert for signs or warnings of "future danger". For example, if it was raining on the day of a car accident, your child might believe that the rain was a "warning" of something bad happening, and refuse to leave the house when it rains.

7. Traumatic play: Similar to very young children, elementary school children may compulsively repeat the trauma in their play. For example, a child who was traumatized by a car accident may then play with toy cars, and have them crash in to each other.

8. Parents may notice dramatic changes in their teen, such as a teen who was once a straight “A” student is suddenly failing, or a teen who never used drugs and respected her curfew, is now dressing inappropriately, smoking, and staying out late.

9. Teens with PTSD often show increased aggressive and impulsive behaviours, and are at greater risk of engaging in high risk or reckless behaviors such as drug and alcohol use, speeding, unprotected sex, etc.

PTSD Checklist

INSTRUCTIONS: Below is a list of problems and complaints that people sometimes have in response to stressful experiences. Circle the response that indicates how much you have been bothered by that problem in the past month. Then add up the numbers. If you scored 44 or higher it is possible that you may have PTSD. We strongly recommend that you discuss the issue of PTSD with your therapist or doctor.

- Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Repeated, disturbing

dreams of a stressful

experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Suddenly acting or feeling as if a stressful experience were happening again (as if you were reliving it)?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Feeling very upset when something reminded you of a stressful experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Having physical reactions (e.g., heart pounding, trouble breathing, sweating) when something reminded you of a stressful experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Avoiding thinking about or talking about a stressful experience or avoiding having feelings related to it?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Avoiding activities or situations because they reminded you of a stressful experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Trouble remembering important parts of a stressful

experience?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Loss of interest

in activities that you used to enjoy?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Feeling distant or cut off from other

people?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Feeling emotionally numb or being unable to have loving feelings for those close to you?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

- Feeling as if your

future will somehow

be cut short?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Trouble falling or staying asleep?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Feeling irritable or having

angry outbursts?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Having difficulty concentrating?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Being "super-alert" or watchful or on

guard?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely - Feeling jumpy or easily

startled?

1. Not at all 2. A little bit 3. Moderately 4. Quite a bit 5. Extremely

http://www.ptsdassociation.com/ptsd-self-assessment.php

https://www.cmha.bc.ca/get-informed/mental-health-information/ptsd

http://www.anxietybc.com/parenting/post-traumatic-stress-disorder

The Window of Tolerance:

The importance of a the window of tolerance in the treatment of trauma

by Carmen Littlejohn

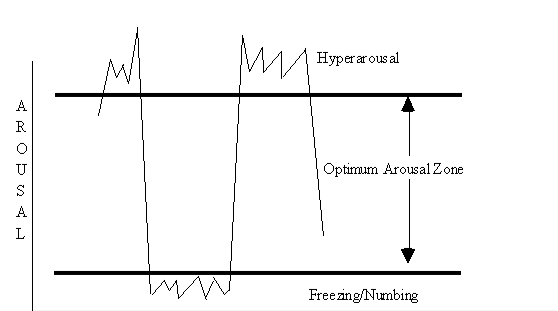

The window of tolerance is a tool that is helpful to understand arousal and the nervous system’s reaction to danger. The top and bottom lines, of the diagram below, depict the limits of a person's optimum degree of arousal. When arousal remains within this zone, a person can process information effectively, maintain their understanding of what is happening, and not dissociate or numb from the emotions, sensations, and thoughts that occur during their experience. In times of danger, we will naturally go outside of the window to mobilize with our fight or flight. In a healthy system, when the danger is over, we’ll return back to within the window. When trauma happens or when we spend extended periods of time outside of this window, we may not be able to regulate our arousal back into the window effectively.

Hyper-arousal, above the top line of the diagram, can lead to increases in heart rate and respiration, as a pounding sensation in the head, anxiety, insomnia, and exhaustion. Over the long term, hyper-arousal may disrupt cognitive and emotional processing as the individual becomes overwhelmed and disorganized by the accelerated pace of thoughts and emotions, which may be accompanied by intrusive memories, hyper-vigilance, panic and PTSD symptoms.

Hypo-arousal, below the bottom line of the diagram, can show up as a decrease in heart rate and respiration and as a sense of numbness and shutting down. Hypo-arousal can manifest as lethargy, lack of interest, chronic fatigue, a dulling of body sensation, slowing of reaction time, and a lack of cognitive and emotional processing.

Both hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal often lead to dissociation. Some of the long term and debilitating symptoms might include emotional dysregulation, social isolation, anhedonia, a sense of isolation, depression, lack of motivation, psychosomatic disorders, and dissociative states. The traumatized individual may live either above or below the optimum arousal zone, or swing uncontrollably between these two states. This alternation between hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal may become their regular state after trauma.

Poor control of their nervous system is characteristic of traumatized individuals. People with a history of trauma, may have very small windows of arousal, meaning any arousal could send them outside their window. Our work as therapists is to help them increase the size of their window tolerance and learn to effectively modulate their arousal back inside. It is important for clients and therapists to understand the window of tolerance. Any time the client is too far outside of their window, processing cannot happen and re-traumatization can inadvertently occur.

In Phase 1 treatment, clients must first learn skills and techniques to modulate arousal so that when dysregulated, they can return inside the window of tolerance. Once arousal is thus stabilized, clients can expand their window of tolerance by working in Phase 2, with reprocessing traumatic memories, and working with repressed emotions, and dissociated states. We cannot start Phase 2 prematurely or re-traumatization could occur.

Exercise to regulate arousal to inside the window of tolerance:

- Imagine a good memory. What it is in the memory that makes it feel so good? Find the image that really helps encapsulates the memory. It may be your dog, the beach, or a sunset. Get an image of it and notice what happens when you focus on that image. What happens in your body? What happens with your posture? Are there any emotions that come with the image? Just notice let your body really FEEL the image.

- This image is now your touchstone. Practice pulling up this image and letting your body feel good. This is called developing a resource. This resource is now your tool to use in stressful times.

- Now to work on regulating arousal. On a scale of 0-10, 0 being not disturbing at all and 10 being very disturbing, pick a memory that is about a 3. There should be a little disturbance in remembering it, but not so much that you go into distress.

- As you think about the memory what do you notice? What happens in your body? What emotions are present now as you think about it? What happens to your posture? Spend about 3-5 minutes really noticing what happens.

- Now, interrupt this old memory, and bring back in your touchstone from the previous good memory. See the image and let your body respond to it. See if you can bring back the good feeling from earlier. Are you able to let the disturbing memory go? Are you able to let the feelings of the disturbing memory go? Can you bring yourself back to the good feelings through the touchstone?

- Practice this with different memories until if feels easier and easier. Try it through out your day if you get stressed or disturbed. Does it get easier to bring yourself back to a regulated state? When this skill gets easier, you are now ready to do deeper work with your therapist around the memories that are closer to a 7-10 on the disturbance scale.

Dissociation: Helpful and problematic

By Carmen Littlejohn

What is Dissociation?

Dissociation is a protective mechanism of the brain and nervous system to try and minimize the impact of being overwhelmed. This could happen for many reasons and could look many different ways. Dissociation happens to everyone. The degree of dissociation depends on how overwhelming the incident is to the individual, their window of tolerance to emotion and arousal in the nervous system, and the chronic nature of how often this may happen especially in childhood. Dissociation is on a spectrum. It can range from every day and normal, to severe and chronic. The meaning of dissociation is that we “dissociate” ourselves from the experience. Often, we dissociate ourselves from the feelings or emotions of the situation.

Why is it dependent on the individual?

Because we all have different levels of what overwhelms us. This is called the window of tolerance. This is the window of what we can tolerate before being overwhelmed. The window lies between hyperarousal (sympathetic nervous system) and hypoarousal (parasympathetic nervous system). The window is not fixed; it is malleable and influenced by environmental and relational experiences. Once we are overwhelmed, our integrative capacity is challenged. Meaning we can’t completely process what is happening. If we don’t process everything, then parts of the event are left in our nervous system. If this happens at an overwhelming level, we could display signs of PTSD and other dissociative disorders.

When does dissociation happen?

Dissociation can happen any time we are overwhelmed, even if we don’t realize we are. Dissociation can also become a process that happens automatically over time. We could stay in a dissociated state for long periods of time and not even realize it. It could happen in a car accident. Usually the moment of impact is blanked out. We may have only a foggy memory of what happened or no memory at all. It could happen in any incident that is frightening or overwhelming. For some people this could be a fight or conflict. For others this may be the thought of balancing their check books. It all depends on what has happened in the past and what our associations are to the current event and how well our nervous systems is able to regulate stimulation.

How early can dissociation begin?

Dissociation is very common in children, as their integrative and regulatory abilities are quite limited. Dissociation will be especially prevalent in children that are around loud noises and fighting, constantly changing environments, lack of security or nurturing, children that are left to “cry it out”. Children of alcoholics, parents with mental disorders, children that moved a lot and had to leave friends or family behind, birth trauma, and emotional neglect. These are only a few examples. The earlier that dissociation happens the more chronic it becomes. It can often be the way a person learns “to deal with emotions or arousal”. Instead of processing emotions or arousal, the person learned a long time ago to “disconnect or dissociate from their experience.”

The science of dissociation.

We all have two main parts of our nervous system. One is called the daily living system and one is called the defensive system. The job of the daily living system is to perform the functions of daily life. This includes going to work, raising the children, cooking dinner, shopping, entertaining, and social situations. The job of the defensive system is to protect us and jump in to defend us if needed. It includes the fight, flight, freeze and submit system. The defensive system will work closely with the daily living system to slam on the breaks if someone pulls out in front of us, react in an emergency, or respond to a conflict or crisis that may happen during the day. It also helps us recuperate from the threat. Once the defensive system has protected us, usually there is arousal left over in the system from the fight or fight system functioning. This may include cortisol and adrenalin, shaking, trembling, difficulty thinking, etc. Once this arousal has left the system, usually the defensive system can let go or re-set, and the daily life system can kick back in. If this arousal is not adaptively processed and is left in the system, the defensive system will store anything left over and not processed. Unfortunately, this left over arousal can cause us problems.

The problem with this left over arousal is that over time it can become a problem. Emotions, images, arousal hormones and chemicals, sensations, cognitive thoughts and defensive actions all can get left in the system. The defensive system is always trying to fix this and get rid of this left over residue. But because our nervous system was overwhelmed at the time of the incident, it can’t adaptively process it out. So it cycles it over and over, often getting triggered by events in the present that may have similarities to events in the past. It affects how we see the world, perceive threat, and process our options at any given moment. It is stored as mal-adaptive information that will impact our view of “reality”.

The daily living system can’t tolerate all of the intrusion of this material. Therefore, it has to try to pull away from the defensive system and instead of working together, harmoniously, they end up having a divide between them. This divide is called the dissociation barrier. It’s the attempt of the daily living system to defend against the intrusion of the defensive system. Over time, this divide could get quite large and create complex systems to keep it in place. This could lead to dissociation disorders, psychosomatic issues, health issues, autoimmune disorders, mental health issues, anxiety, numbness, and a limited ability to function in daily life.

Summary: (Martin, Kathy. MSW, EMDR facilitator. Rochester, NY)

if The Daily Living Action System and the Defensive Action System cooperate, communicate and work together, the person functions well.

- Trauma impairs this coordination. A traumatic experience overwhelms the person’s integrative capacity .

- The person is flooded by the emotions, arousal, and somatic information and can’t fully process, synthesize and integrate this information.

- The daily living action system must continue with daily activities while the defensive action system manages the unhealed emotions and information.

- To attend to daily activities, the daily living action system must “tune out” the defensive action system

- To manage the unhealed hurt, the defensive action system becomes stuck in “trauma time” and does not realize the present

Daily Living System

The daily living system needs to pay attention to daily activities and:

· Avoid the physical and mental trauma-related cues and info held by the Defensive System

· Become detached from the full experience

· Appear undisturbed and able to lead a normal life

· Can’t help process and integrate the event while also engaging in avoidant behavior

Defensive System

The defensive action system stores, manages and relives the traumatic material.

- It is fixated in the traumatic material

- Relives the emotional and behavioral responses used (and not used) during the traumatic event

- Holds and relives the catastrophic beliefs and negative thoughts about self in response to the trauma: e.g., “It’s my fault”, “I’m not safe”, “I’m bad”

- May be stuck in defensive actions such as fight, flight, freeze, collapse, submit, attachment cry

- Can’t contribute to the processing and integration of the traumatic material while stuck in “trauma time

Can this be treated and how?

Yes. EMDR is one of the best ways I’ve seen to treat the dissociation in order to get to the trauma. We often need to treat the dissociation before we can access the trauma in order to process out the left over material or residue. This is important to return to good mental health. Any dissociation related disorder such as PTSD, chronic anxiety, phobias, perseverating on past events, feeling like a small child, any unremitting symptom that doctors or naturopaths are having trouble finding a cause of solution to, chronic fatigue, adrenal fatigue, high levels of cortisol, often needs to have dissociation treated before the trauma can be processed. Even if you don’t know what the trauma is, that is ok, there is often left over residue from events that you may not realize were traumatic. Often people that have trauma from events in the past or childhood, don’t realize they were traumatized or carry left over material from these events.

Not every EMDR therapist is trained in dissociation work. Make sure you ask. Working with dissociation can be very specific work and if a person has a lot of dissociation and it is left untreated, psychotherapy and talk therapy can actually cause adverse effects, or an increase in symptomology. I’m happy to give referrals of therapists that are trained in dissociation work, especially in the Toronto area. It is important to know that dissociation can be completely healed. If you’ve been in therapy for a long time and have not had a lot of success or hit a wall with it, you may have dissociation and it just hasn’t been treated yet. Often once this is done, you can work with the trauma in a much more direct and graceful way.